The History of the Underlying Technologies Behind Internet Business Directories and Maps

It is difficult to overstate how profoundly the ability to find a business and locate it on a map has changed in the last three decades. For the better part of a century, this process was physical, heavy, and static. It involved a four-pound book of yellow paper and a folded roadmap that never quite went back into the glovebox correctly. Today, it is instantaneous, predictive, and dynamic.

This transformation was not a single invention but a collision of distinct technological lineages: the digitization of commercial databases (business directories) and the democratization of Geographic Information Systems (digital maps). For a long time, these were separate worlds. The history of their convergence is a story of technical ingenuity, fierce corporate warfare, and the relentless pursuit of “ground truth.”

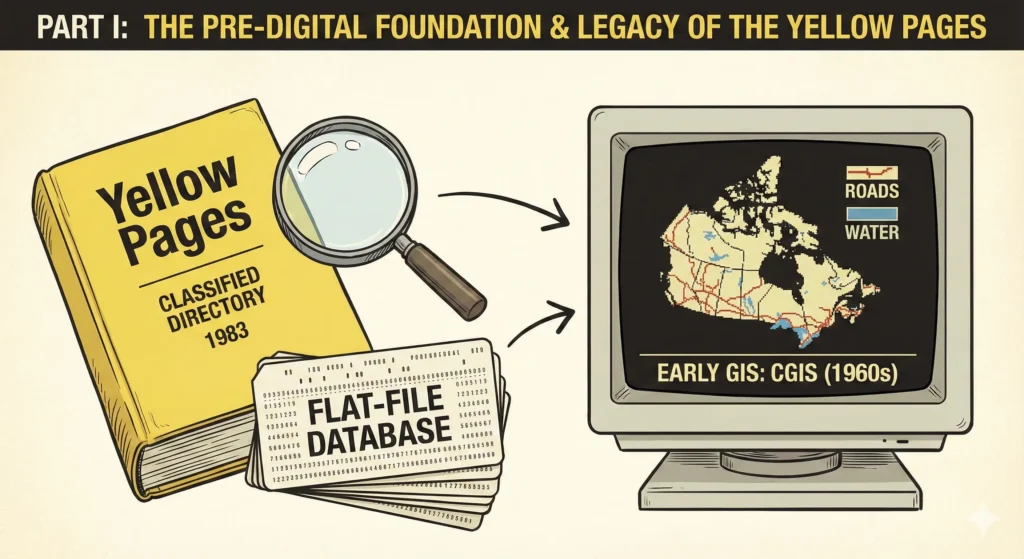

Part I: The Pre-Digital Foundation

The Legacy of the Yellow Pages

To understand the digital business directory, one must understand its analog ancestor. The concept of the commercial directory dates back to 1883 in Cheyenne, Wyoming, when a printer ran out of white paper and used yellow stock instead. But the true titan of the industry was Reuben H. Donnelley, who established the first official Yellow Pages in Chicago in 1886.

Technically, the Yellow Pages was a marvel of data organization before computers. It relied on a strict taxonomy—a categorization system where a business had to declare its primary function. This taxonomy (Plumbers, Pizza, Locksmiths) would later form the backbone of early internet directories.

By the 1980s, the production of these books had already been digitized, even if the product remained paper. Publishers like R.R. Donnelley & Sons utilized massive mainframe computers to store business names, addresses, and phone numbers (NAP data). These databases were flat-file systems, rigid and difficult to query dynamically, but they held the raw ore that would eventually fuel the internet boom.

Early GIS: The Computerization of Geography

Parallel to the directory business, the world of cartography was undergoing its own quiet revolution. In the 1960s, Roger Tomlinson developed the Canada Geographic Information System (CGIS), generally recognized as the world’s first GIS. Before this, maps were hand-drawn static images. GIS turned maps into data—layers of information (roads, water, elevation) stored numerically.

In 1969, Jack Dangermond founded the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri). While Esri focused on professional land-use planning, their work established the fundamental data structures for digital mapping:

- Vector Data: Representing the world as points, lines, and polygons (mathematical descriptions of shapes).

- Raster Data: Representing the world as a grid of pixels (like a digital photo or satellite image).

The Pre-Digital Foundation

Two parallel worlds before convergence

Key Insight: For nearly a century, business directories and geographic mapping existed as separate technological domains. Directories focused on what (businesses and services), while GIS focused on where (locations and spatial relationships). Their convergence would require solving the challenge of delivering complex spatial data over limited bandwidth.

For decades, these technologies were too computationally expensive for consumers. A single digital map required the processing power of a workstation. The challenge of the impending internet age would be figuring out how to deliver this complex spatial data over a 56k dial-up modem.

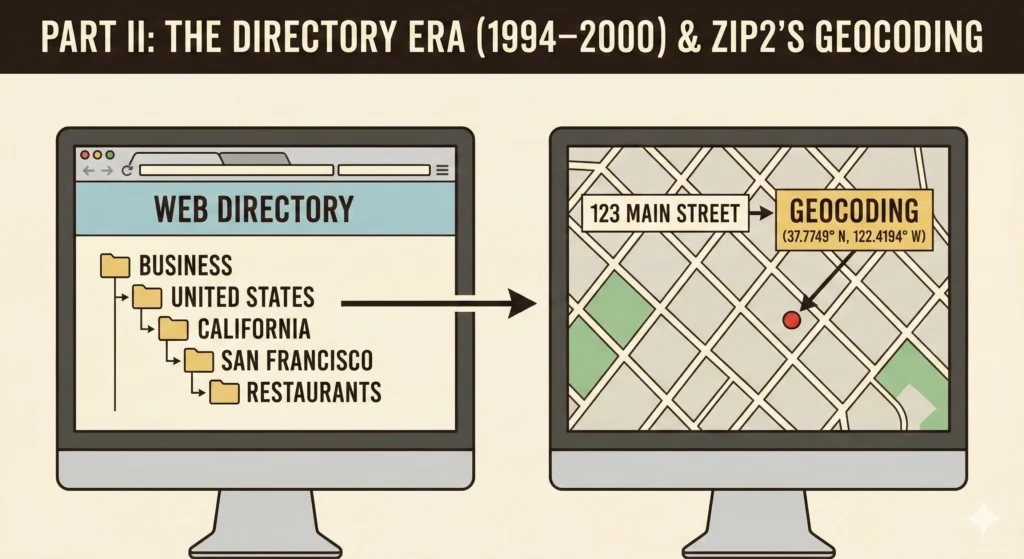

Part II: The Directory Era (1994–2000)

The Rise of the “City Guide”

As the World Wide Web emerged in the early 1990s, the first attempt to organize the chaos was the “Directory.” Unlike modern search engines that crawl the web automatically, directories were hand-curated lists.

Yahoo! (founded in 1994 by Jerry Yang and David Filo) was the most famous example. Technically, Yahoo! was a hierarchical ontology. Human editors would manually review websites and slot them into categories: Business > United States > California > San Francisco > Restaurants.

The underlying technology was relatively simple: a tree-structure database that users navigated by clicking down through branches. This mirrored the cognitive model of the Yellow Pages. You didn’t “search” for a plumber; you “looked up” plumbers.

Zip2: Elon Musk and the Vector Database

While Yahoo organized the web, a small startup in Palo Alto called Zip2 (founded in 1995 by Elon and Kimbal Musk) attempted to put the physical world online. Zip2 is crucial to this history because it was one of the first instances of merging a business directory database with a vector mapping database.

Elon Musk coded much of the original system himself. The technical innovation was linking a business address (from a purchased yellow pages database) to a latitude/longitude coordinate, a process known as geocoding.

- The Challenge: Digital maps at the time didn’t know where “123 Main Street” was. They only knew that a line segment representing “Main Street” started at coordinate A and ended at coordinate B, and that the address range was 100–200.

- The Solution: Linear Interpolation. If “123 Main Street” is 23% of the way through the address range, the software plotted the point 23% of the way along the line segment.

Key Innovation: Zip2’s breakthrough was geocoding—linking business addresses to map coordinates using linear interpolation. If “123 Main Street” fell 23% through the address range (100–200), the system plotted it 23% along the street segment. This technical solution enabled the first practical merger of business directories with digital maps.

Zip2 licensed this software to newspapers, allowing them to create “City Guides.” It was a primitive precursor to Google Maps, but it proved that the utility of the internet lay in connecting users to the physical economy. Compaq acquired Zip2 in 1999 for over $300 million.

The integration of mapping technologies with business directories reached a significant milestone in 1995 with Zip2, founded by Elon Musk and his brother Kimbal Musk. Zip2 provided newspapers with a platform to create searchable business directories with integrated mapping capabilities, marking the first major commercial application of geographic information systems (GIS) in business directory services.

This integration represented a fundamental shift from text-based directory listings to geographically-aware systems that enabled users to:

– Visualize business locations on interactive maps

– Calculate distances and plan routes between businesses

– Filter businesses by geographic proximity

– Combine directory search with mapping functionality

The Zip2 platform demonstrated the commercial viability of combining business directory data with mapping technology, influencing the development of subsequent directory platforms including Google Maps and modern location-based services.

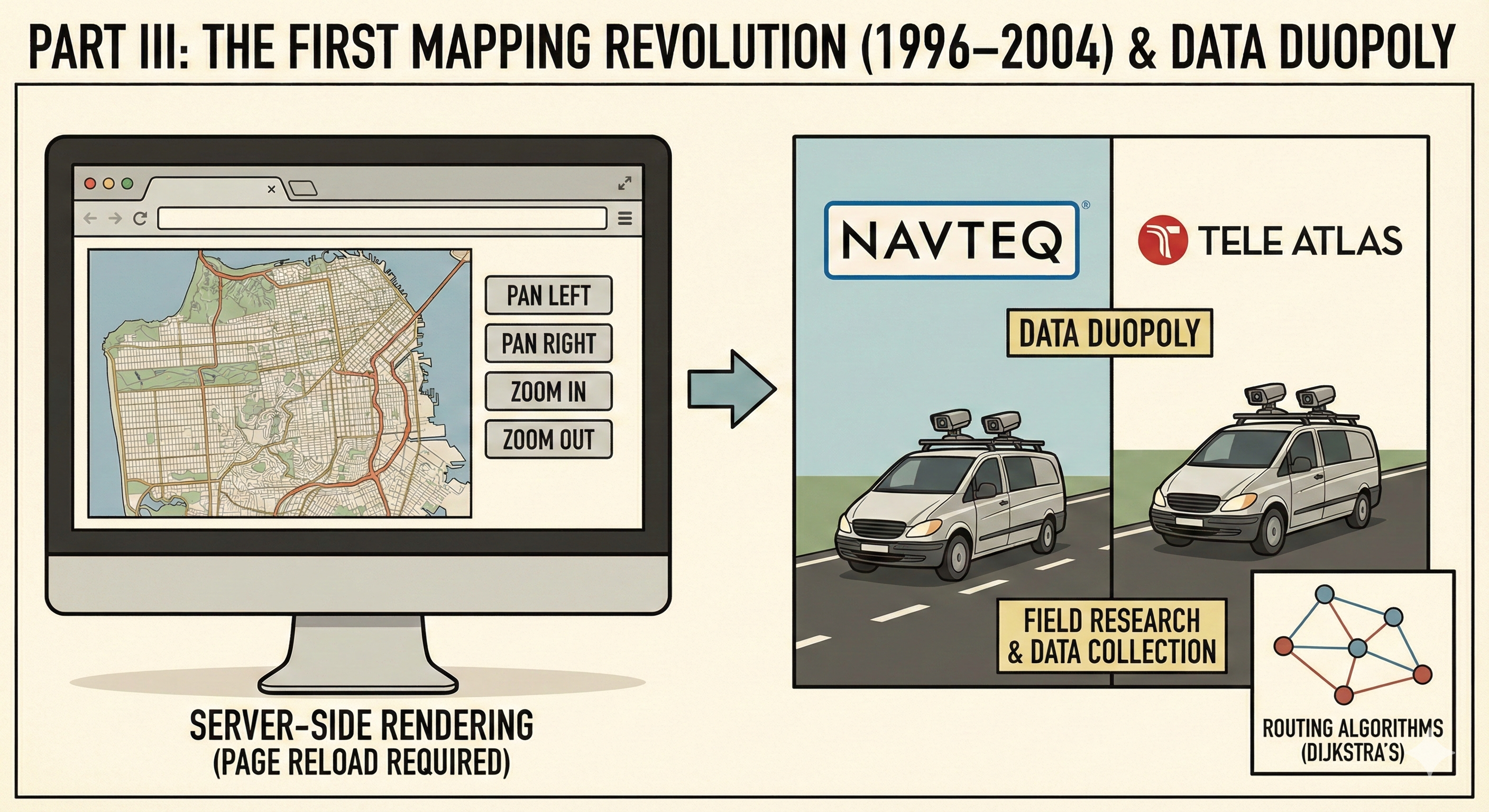

Part III: The First Mapping Revolution (1996–2004)

MapQuest: The Raster King

If you printed driving directions in 1999, you used MapQuest.

MapQuest began as a cartographic division of R.R. Donnelley (the Yellow Pages printer) called GeoSystems Global. They spun off in 1994 and launched MapQuest.com in February 1996.

The Technology: Server-Side Rendering

MapQuest’s dominance was built on a technology that, by modern standards, was clunky. When a user requested a map:

- The request (center point, zoom level) was sent to the MapQuest server.

- The server’s GIS software would generate a single, custom raster image (a GIF or JPEG) drawing the roads and labels for that specific view.

- This entire image was downloaded to the user’s browser.

If the user wanted to pan right, they clicked a “Right” arrow. The browser sent a new request to the server, the server generated a new image, and the entire page reloaded. It was slow and disjointed, breaking the user’s cognitive flow. However, it was the first time the general public had access to dynamic routing algorithms.

Routing Algorithms:

Behind the scenes, MapQuest used a variation of Dijkstra’s algorithm, a graph theory method for finding the shortest path between nodes. The road network was stored as a “graph”—a collection of nodes (intersections) and edges (roads). Each edge had a “weight” based on distance and speed limit. The server calculated the path with the lowest total weight.

Key Insight: MapQuest’s server-side rendering was clunky by modern standards (full page reloads for each pan), but it democratized access to dynamic routing. Behind the scenes, Dijkstra’s algorithm calculated optimal paths through road networks. The real “underlying technology” was the expensive, physically-collected road data from Navteq and Tele Atlas—a duopoly that created massive barriers to entry.

The Data Duopoly: Navteq vs. Tele Atlas

While MapQuest provided the interface, they did not own the road data. The “underlying technology” of digital maps is arguably the data itself. During this era, a global duopoly emerged:

- Navteq: Based in the US (Chicago).

- Tele Atlas: Based in Europe (Netherlands).

These companies didn’t just trace satellite photos. They employed thousands of field researchers who drove vans equipped with multiple cameras, GPS units, and hard drives. They were physically digitizing the world, recording speed limits, turn restrictions (“No Left Turn 4PM-6PM”), and one-way streets. This data was incredibly expensive to collect and maintain, creating a massive “moat” that prevented startups from entering the mapping space.

Part IV: The AJAX Revolution and the “Slippy Map” (2005)

The year 2005 marked the extinction event for the “click-arrow-to-pan” era. The meteor was Google Maps.

The Acquisitions: Keyhole and Where 2 Tech

Google did not build Google Maps entirely in-house. They acquired two critical startups in 2004:

- Keyhole, Inc.: Co-founded by Brian McClendon, Keyhole built “EarthViewer,” a 3D visualization tool that streamed terabytes of satellite imagery over the internet. This became Google Earth.

- Where 2 Technologies: Founded by Danish brothers Lars and Jens Rasmussen. They had the idea for a mapping application that didn’t reload the page.

Key Innovation: Google Maps combined pre-rendered tiles (quadtree structure) with AJAX (background data fetching) to create the “Slippy Map”—a seamless, draggable experience that felt infinite. Instead of generating custom images on-demand like MapQuest, Google pre-rendered millions of 256×256 pixel tiles and fetched only the ones needed for the current viewport. This became the industry standard overnight.

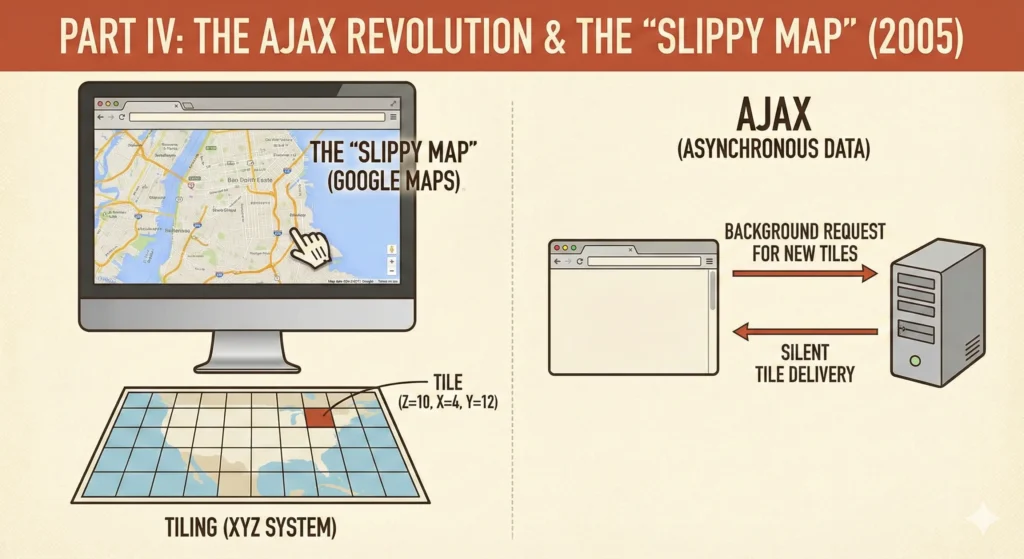

The Technical Breakthrough: AJAX and Tiling

When Google Maps launched in February 2005, it introduced the world to the “Slippy Map”—a map you could drag with your mouse seamlessly. This was made possible by two key technologies:

1. Tiling (The XYZ System)

Instead of generating one giant custom image for every user request (like MapQuest), Google pre-rendered the entire world into millions of small, static square images, typically 256×256 pixels.

- Zoom Level 0: The whole world in one tile.

- Zoom Level 1: The world divided into 4 tiles.

- Zoom Level 2: The world divided into 16 tiles.

This is known as a Quadtree data structure. When a browser requests a map, it simply asks for the specific pre-made JPEGs for that viewport (e.g., tile_x=4, tile_y=12, zoom=10). This was infinitely faster than generating a new map on the fly.

2. AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML)

Before 2005, if a browser needed new data, it had to reload the page. Google Maps utilized XMLHttpRequest, a hidden browser capability that allowed JavaScript to talk to the server in the background.

As a user dragged the map, the JavaScript calculated which new tiles were coming into view and fetched them silently. By the time the user dragged the map further, the tiles were already there. This created the illusion of a continuous, infinite surface.

This combination—Pre-rendered Tiles + AJAX—became the industry standard almost overnight. It is still how virtually all web maps work today.

Performance optimization in business directory platforms is measured through several key metrics:

– Database query optimization: Strategic indexing can reduce query execution time from 200-500ms to 20-50ms for common filtered searches, representing a 75-90% performance improvement.

– Page load performance: Asset bundling and optimization (combining multiple CSS/JS files into single bundles) can reduce HTTP requests from 10+ files to 2 bundled files, improving page load scores by 15-20 points on standard performance testing tools (Pingdom, GTmetrix).

– Caching effectiveness: WordPress object cache implementation can reduce database queries by 60-80% for frequently accessed directory pages, with cache hit rates typically exceeding 85% for popular listings.

– Import performance: CSV/XLSX import systems can process 1,000-5,000 business listings in 30-60 seconds, with automatic validation and error reporting for data quality issues.

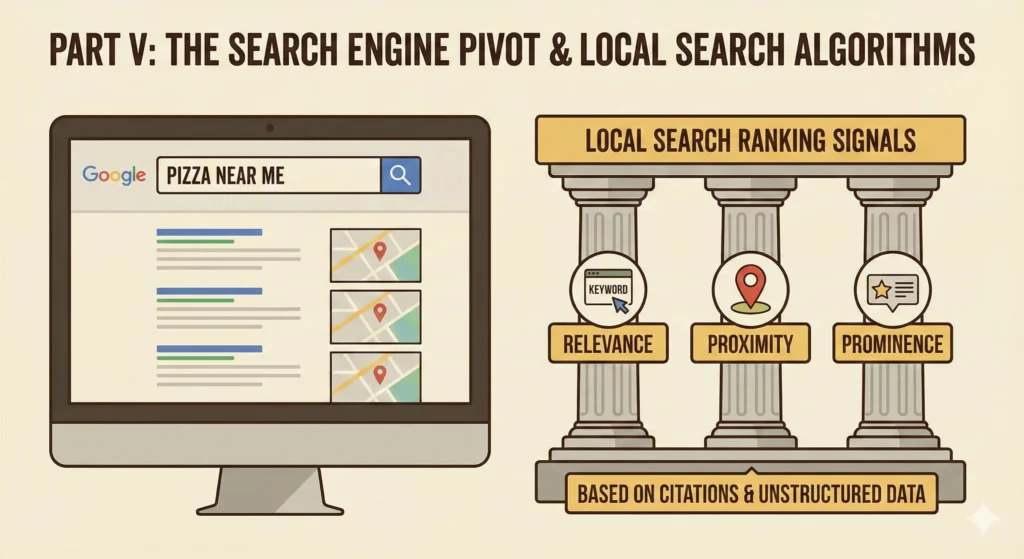

Part V: The Search Engine Pivot – “Local Search”

With the map interface solved, the challenge returned to the directory. The Yellow Pages model (categories) was failing. Users didn’t want to browse “Restaurants > Italian”; they wanted to type “Pizza near me” into a search box.

From Structured Data to Unstructured Retrieval

Traditional directories relied on structured SQL databases. Search engines like Google excelled at unstructured text retrieval. Google Local (later Google Places/Maps) merged these approaches.

Key Innovation: Local Search merged structured directory data with unstructured text retrieval. Instead of browsing categories, users could type natural queries like “Pizza near me.” The algorithm ranked results using three signals: Relevance (category match), Proximity (distance from user), and Prominence (citations, reviews, check-ins). Google crawled the web for NAP citations—when multiple sites mentioned the same business address, it increased confidence in the listing’s accuracy.

The database architecture of modern business directories employs several optimization strategies:

– Strategic database indexing: Directory platforms implement indexes on fields commonly used in WHERE clauses, including geographic fields (country, state, city), categorical fields (business_niche), and search fields (slug, business_name). These indexes typically reduce query execution time by 50-80% for filtered searches.

– Custom field systems: Advanced directory platforms implement WordPress-style meta API systems for custom fields, allowing flexible data storage beyond the core listing schema. This enables directory administrators to add custom attributes specific to their industry or use case without modifying the core database structure.

– Prepared statements and security: Modern directory platforms use 100% prepared statements for all database queries, eliminating SQL injection vectors. All user inputs undergo field-specific sanitization before database operations, with output escaping using context-aware functions (esc_html, esc_url, esc_attr).

– Database optimization tools: Enterprise directory platforms include built-in database optimization tools that allow administrators to view table statistics, manage indexes, and optimize table structures. These tools help maintain performance as directory size grows.

The “Local Search” algorithm introduced a new ranking paradigm distinct from standard web search (SEO). While web search ranked pages based on keywords and backlinks, Local Search used three primary signals:

- Relevance: How well does the business category match the query?

- Proximity: How close is the business to the user’s IP address or GPS location?

- Prominence: How “important” is this place? (measured by citations across the web, reviews, and later, check-ins).

This required Google to crawl the web not just for links, but for Citations—mentions of a business’s Name, Address, and Phone number (NAP). If a thousand websites mentioned “Joe’s Pizza at 123 Main St,” Google’s algorithm increased the confidence that Joe’s Pizza actually existed at that location.

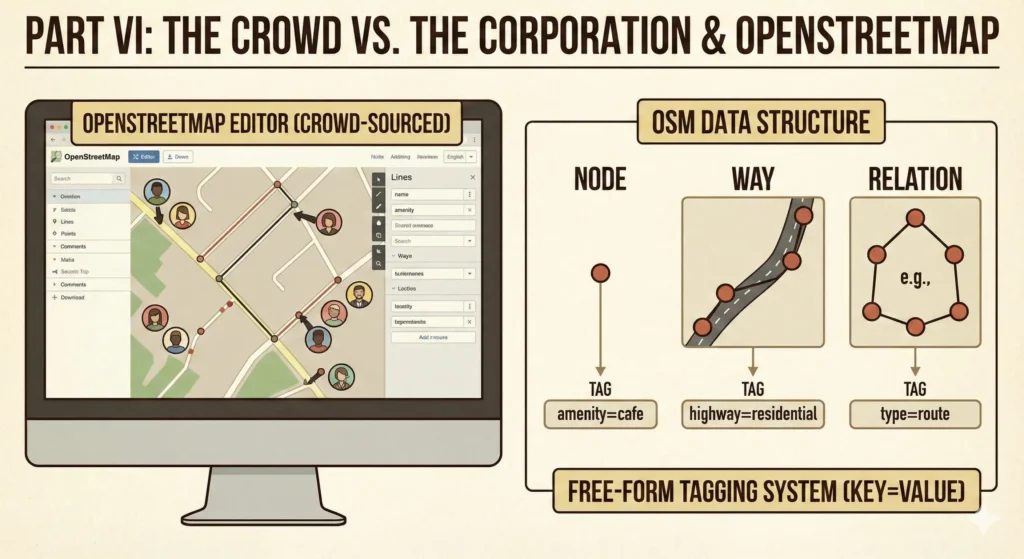

Part VI: The Crowd vs. The Corporation

OpenStreetMap (OSM)

By the mid-2000s, the data duopoly (Navteq/Tele Atlas) was stifling innovation. Their data was prohibitively expensive. In 2004, Steve Coast, a British physics student, founded OpenStreetMap with a radical idea: What if we mapped the world like we write Wikipedia?

The Technology: Topological Data Structure

OSM does not store “maps”; it stores geographic facts. Its database is built on three primitives:

- Nodes: Points in space (latitude/longitude).

- Ways: Ordered lists of nodes (forming roads, rivers, or building outlines).

- Relations: Groups of nodes and ways (e.g., a bus route that consists of many streets).

Crucially, OSM uses a free-form Tagging system (Key=Value). A user can tag a node as amenity=cafe and wifi=free.

Volunteers initially used handheld GPS units to record “traces” (breadcrumbs of movement) and then traced roads over them. Later, Yahoo! and eventually Bing allowed OSM to trace over their aerial imagery. Today, OSM is the backend for thousands of applications (including Craigslist, Foursquare, and even parts of Apple Maps), providing a free alternative to the corporate giants.

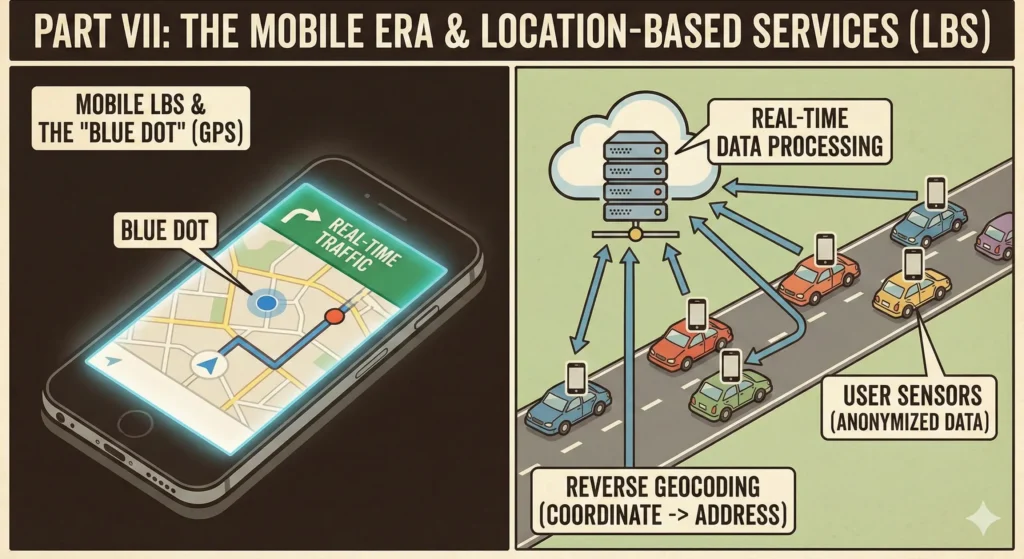

Part VII: The Mobile Era and Location-Based Services

The final piece of the puzzle fell into place with the launch of the iPhone (2007) and Android (2008).

GPS and the Blue Dot

Prior to smartphones, “Location” was something you typed into a computer. With the integration of GPS (Global Positioning System) chips into phones, “Location” became a passive, always-on state.

The technology shifted from Geocoding (Address -> Coordinate) to Reverse Geocoding (Coordinate -> Address). When you open Uber, your phone sends your lat/long to a server, which queries a spatial database to determine, “This coordinate is on 5th Avenue.”

Modern Database-Driven Directory Platforms

Modern business directory platforms demonstrate the practical application of database-driven architectures through several key implementation patterns:

– Relational database optimization: Directory platforms utilize relational databases (typically MySQL or MariaDB in WordPress environments) with custom schemas optimized for directory operations. These schemas include fields for geographic data (latitude, longitude, country, state, city), business attributes (niche, rating, verification status), and metadata (created_at, updated_at timestamps).

– API integration patterns: Modern directory platforms integrate with external APIs for mapping (Mapillary, OpenStreetMap), geocoding (converting addresses to coordinates), and data enrichment. These integrations are implemented using WordPress’s HTTP API with proper error handling, rate limiting, and caching to ensure reliability and performance.

– Mobile-responsive design: Contemporary directory platforms implement responsive design patterns using CSS Grid and Flexbox, with mobile-specific optimizations including touch-friendly interfaces, optimized image loading, and reduced JavaScript execution on mobile devices. Glass card design patterns provide visual depth while maintaining performance.

– Review and rating systems: Advanced directory platforms include customer review systems with image upload capabilities, rating aggregation algorithms, and moderation workflows. These systems store review data in separate database tables with foreign key relationships to business listings, enabling efficient querying and display of review information.

Real-Time Data and Traffic

The loop closed when users became the sensors. In the early days, traffic data came from physical sensors under the pavement. With the widespread adoption of Google Maps and Waze (acquired by Google in 2013), the “speed of traffic” was calculated by aggregating the velocity of millions of Android phones moving down the highway.

This required massive stream-processing architectures (like Apache Kafka or Google’s internal tools) capable of ingesting millions of pings per second, anonymizing them, and updating the “edge weights” of the routing graph in real-time.

The Final Revolution: Smartphones turned location from something you typed into something that’s always known. GPS enabled reverse geocoding (coordinates → address), creating the “blue dot” that shows where you are. But the real breakthrough was turning users into sensors—millions of phones sending speed and location data created real-time traffic information. Stream processing architectures (Apache Kafka, Google’s internal tools) aggregate these millions of pings per second, anonymize them, and update routing graph edge weights in real-time. The loop closed: users became both consumers and producers of location data.

WordPress-Based Directory Platforms: Modern Database-Driven Architecture

WordPress-based business directory platforms represent a significant modern implementation of database-driven directory architecture. These platforms utilize custom database tables optimized for directory-specific operations, moving beyond WordPress’s standard post and meta tables to create dedicated schemas for business listings.

Key technical features of WordPress directory platforms include:

– Custom database tables with strategic indexing: Modern WordPress directory plugins implement custom database tables (typically prefixed with the plugin identifier) that include indexes on common query fields such as business_niche, country, state, city, and slug. These indexes enable efficient geographic and categorical filtering, with query performance improvements of 15-20 points on standard performance metrics.

– CSV/XLSX import capabilities: Enterprise-level directory platforms support bulk data import through CSV and XLSX file formats, utilizing libraries such as PhpSpreadsheet to parse and validate imported data. This functionality enables directory administrators to import thousands of business listings in a single operation, with automatic data validation and error reporting.

– Dynamic virtual page generation: WordPress directory platforms implement custom rewrite rules to generate virtual pages for individual business listings, following URL patterns such as `/business/[business-name]/` or more complex structures like `/[business_niche]/[country]/[state]/[city]/[business_name]/`. These virtual pages are generated dynamically from database queries rather than stored as individual WordPress posts, enabling efficient management of large-scale directories.

– Integration with mapping services: Modern WordPress directory platforms integrate with multiple mapping APIs, including Mapillary for street-level imagery and OpenStreetMap for base mapping data. This integration enables geographic visualization of business locations without reliance on proprietary mapping services.

– Performance optimization: WordPress directory platforms implement various performance optimizations including object caching (using WordPress’s built-in caching API), lazy loading for map components, critical CSS in lining, and font-display optimization. These optimizations are particularly important for directories with thousands of listings, where database query efficiency and asset loading speed directly impact user experience.

Conclusion

The history of internet directories and maps is a journey from static lists to living models of the world. We moved from the Yellow Pages (static text) to MapQuest (static images), to Google Maps (interactive tiles), and finally to Real-time LBS (live traffic and predictive AI).

What began as a printer trying to save money on white paper in 1883 has evolved into a digital nervous system for the planet. The underlying technologies—spatial databases, AJAX, tile rendering, and crowd-sourced vectors—have not just mapped our world; they have fundamentally changed how we navigate it. We no longer plan journeys; we simply embark, trusting the invisible handshake of satellites and servers to guide us.